Free Shipping to the Contiguous United States

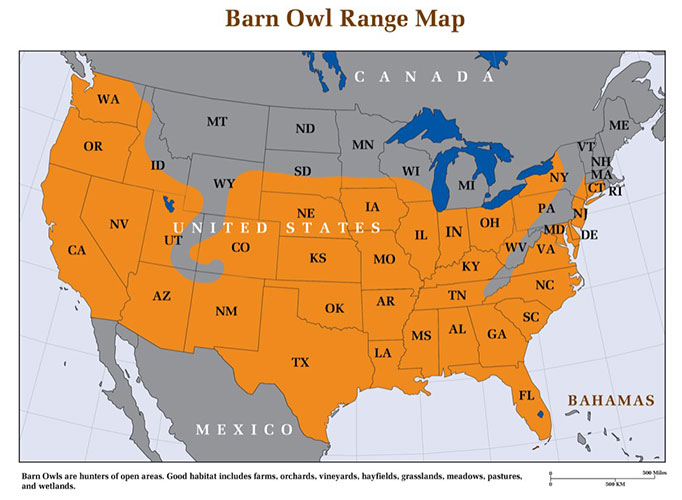

Post Gazette Reports Satellites Will Keep An Eye On Barn Owls

The Pittsburgh Zoo and PPG Aquarium’s barn owl program has seven babies and two adults being raised at a private Fox Chapel location. They will be released into the wild with transmitters

Sixteen barn owls that were bred in captivity will be carrying some baggage when they are released into the wild tomorrow.

For the first time, transmitter harnesses will be put on the birds so that satellites can track them.

“That gives us a really good chance to find out where they’re going,” said Mark Browning, animal trainer and head of the barn owl release project at the Pittsburgh Zoo and PPG Aquarium.

Eight of the 11 birds that the zoo will release in Fox Chapel tomorrow will carry trackers. The Moraine Preservation Fund will put devices on another eight birds that will be released from Moraine State Park.

The project is part of an effort to re-establish barn owl populations in Western Pennsylvania. Partly because they’re nocturnal, it’s hard to tell how many of them are in the region.

According to director Heather Cuyler Jerry, the preservation fund has released about 250 birds in the last seven years, but doesn’t have much information about how they’ve fared since they were released from captivity.

Data from the satellite telemetry project, which was partly funded by a grant from the Pittsburgh Foundation, could help shape the barn owl program in coming years by revealing favored nesting areas, she said.

The trackers “will transmit for about nine months and give us an opportunity to see what kind of territory they [barn owls] reject and what kind of territory they accept,” Browning said.

Dan Brauning, wildlife diversity supervisor for the state game commission, was excited to hear about the project.

“They’re doing satellite telemetry? Wow!” he said. “From a research standpoint, it’s absolutely the right thing to do.”

Browning said the harness is an intricate sling of Teflon ribbons that, like a parachute harness, wraps around above and below the bird’s wing and meets at the back. A fine antenna curves behind the bird, where it should not hinder normal activities.

When it was first put on, the equipment was easy to spot. The transmitter is about 2.5 inches long and weighs a little more than half an ounce.

Now, “all you see is the antenna because they’ve been systematically preening everything in,” Browning said. “So now they’re cool and everything is hidden.”

He is working with Frank Ammer, a DNA specialist at Frostburg State University in Maryland to collect blood samples from owls that are about to be released.

So, “if we eventually go out there and find a nest of baby birds and take blood from one of them, we may be able to tell if it’s related to one of ours,” Browning said.

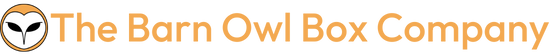

Barn owls were probably a rare bird when pioneers first came to a heavily forested Pennsylvania.

The numbers likely increased dramatically because people “cleared the fields where barn owls like to hunt, they probably created higher populations of rodents and they built beautiful wooden barns where barn owls could nest easily,” Browning said.

But the few barns that are built now tend to be metal prefab buildings that owls can’t call home, and the population has dwindled.

Conservationists like Browning would like to see the population grow and, to help boost it, they have not only bred baby owls for release into the wild, but also provided them with nest boxes to live in.

A good nest box, Browning explained, is about 30 inches long, more than a foot high and about 2 feet deep. That should be enough room for the parents and a clutch of about a half-dozen babies. Barn owls can be nearly 2 feet tall.

“As tall as they are and as big as they look, they only weigh about 1 pound,” he noted. “They’re a lot of fluff.”

The zoo has three breeding pairs. One is kept at the Highland Park facility, in a newly built exhibit near the Kid’s Kingdom. Another pair is housed by the National Aviary on the North Side.

A third duo and their seven young, about 90 days old, are kept at a specially built flight on a large private property in Fox Chapel. Four other young owls that were born last fall will also be released from the site.

The open-air cage is partitioned so that when it’s time to let the youngsters go, their breeding pair can still be confined. Boxes for nesting and roosting look the same as those being distributed in the wild to help the owls recognize them as a safe haven.

Since their births, the young owls have been fed frozen mice that have been thawed. But in the days before their release, they must hone their flying, swooping and hunting skills to catch live mice that will be placed in their cage.

Barn owls have a facial disc that is concave and their ears are assymetrical, making their hearing acute enough to pick up mice pitter-pattering across the ground, Browning said.

When the young owls are better hunters, the cage will be left open so they can leave as they wish.

“If they want to fly out and want to come back, they can do that for a week or so,” Browning said. “At some point, I’m going to decide none are coming back or it’s time to close it up and let them go.”

Mark Browning, animal trainer and head of the barn owl release project at the Pittsburgh Zoo and PPG Aquarium.